Very often in the discussions about additive manufacturing, the topic of energy efficiency is brought up, highlighting a shorter logistic chain and improved part properties such as reduced weight or efficiency thanks to better flow or heat distribution. However, the most significant source of energy consumption, the production of metal powders by atomization, is often omitted.

What Fuels Metal AM?

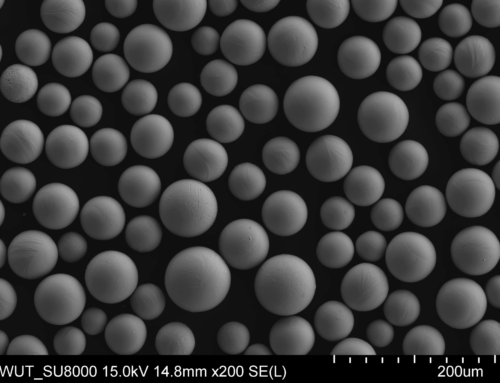

Most metal additive manufacturing (metal 3D printing) is fueled by a single feedstock type, metal powder, composed of micron-sized particles. For AM, typically, the powders are below 100 µm, and most importantly, the spherical shape of powder particles is required for most applications, which can be produced almost exclusively by atomization technology.

Shape is an essential aspect of a powder particle, determining its properties, mainly flowability (cohesivity of the powder. The high flowability of the powder (low cohesivity) allows the powder to create consistent powder layers for powder bed Fusion technologies and consistent flow for applications, such as continuous powder feeding like Directed Energy Deposition (DED) or Cold Spray (CS). This property is essential for running a consistent AM process across the majority of systems.

What’s a Metal Atomization process, and how efficient is it?

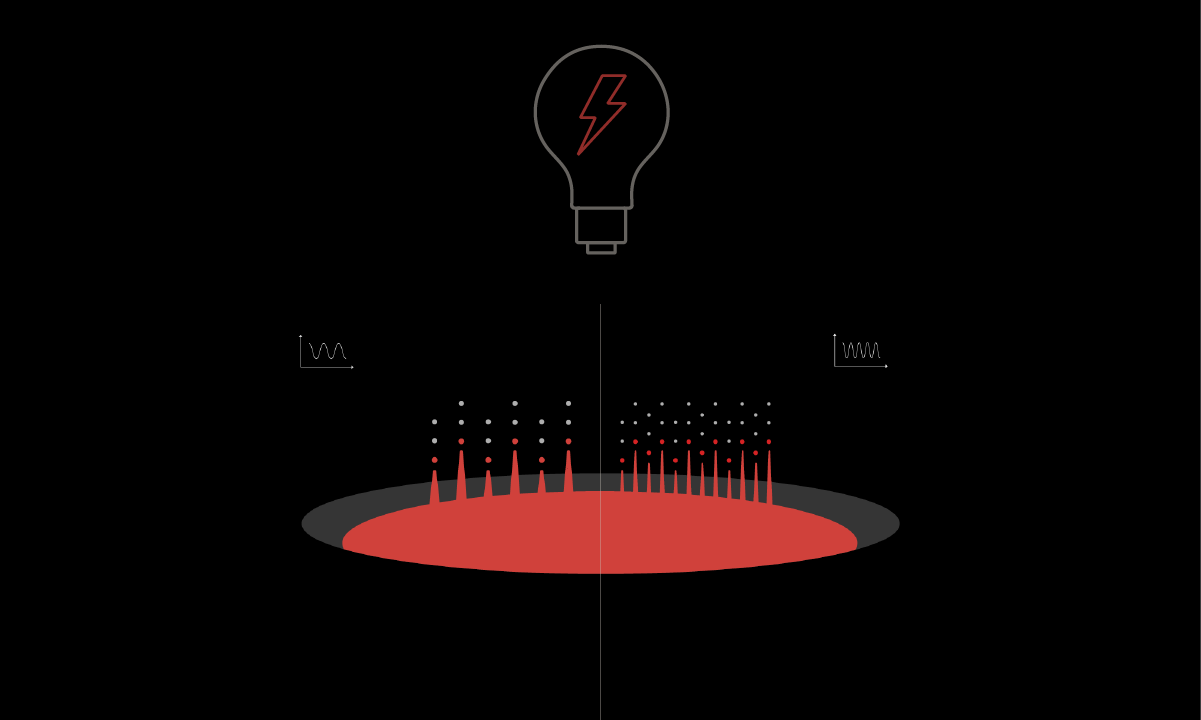

When producing metal powders through atomization, only a tiny fraction of the input energy is actually used to create the new surface area of the particles. In theory, the minimum energy required to form powder can be defined as the surface energy, Sm, the energy needed to generate the total surface area of all particles produced from the molten metal.

In practice, much more energy is consumed during gas atomization processes. Energy is required for:

- Compression of the atomization gas (argon in liquified storage form) to the required pressure – egas.

- Heating gas, especially when warm or hot gas atomization is used to increase the pressure and lower the size of atomized powder particles – Δhgas

- Melting and superheating the metal, ensuring fluidity and avoiding solidification at the nozzle tip – Δhmelt.

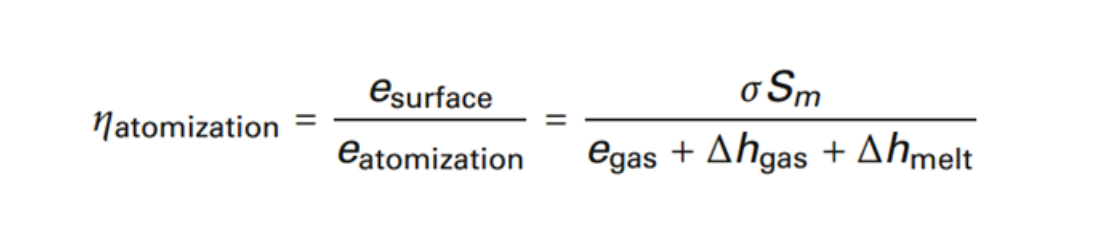

To quantify how efficiently energy is used, we can define the energy efficiency of an atomization process – ηatomization as the ratio between:

- The theoretical surface energy of the powder (i.e., the minimum energy required to create all particle surfaces) – esurface

- The total energy input into the system, including gas pressurization, heating, and metal melting – eatomization

This relationship can be expressed as:

The energy efficiency of gas atomization is extremely low and can be in the range of just 0.0002 – 0.0003%.

In gas atomization processes, the energy to compress the inert gas, Argon, to its liquid form for atomization is the most significant contributor to the energy used during the atomization process. It can account for up to 95% of total energy consumption during the processes, with other factors like energy melting or gas heating contributing only between 5 – 15 %.

Gas atomization uses huge pressures of 20 – 80 bars (2 – 8 MPa), resulting in the use of over 1000 l/min of argon during processes. That’s why, for efficient gas atomization processes, optimized closed-coupled nozzles, inert gas recovery, and other systems lowering gas consumption (like gas heating) and increasing productivity in the specified size range are of most importance. Gas atomization of smaller powder particles requires the use of higher pressure, which significantly increases argon consumption, further increasing energy use and lowering efficiency.

The argon gas usage for ultrasonic atomization is far lower – 10 l/min compared to gas atomization, and coupled with the low power needed for ultrasonic systems <500 W, helps to improve the energy efficiency of ultrasonic atomization to ~ 0.0025 %. This is, however, still offset by the limited productivity <1 kg/h of ultrasonic atomization compared to gas atomization, making it the most efficient and viable technology for low volume powder production typically below 50 kg.

How particle size range you use influences the energy required for atomization

Precise applications such as Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF)—also known as Powder Bed Fusion–Laser Beam Melting (PBF-LB/M) us tighter, more controlled size range of metal powders – the 15-63 µm used to be a standard, which transformed in recent years to a tighter range of 15-45 µm or 15-52 µm to better correspond to the most often used powder layer height range in LPBF of 30-50 µm achieve lower surface roughness. Other technologies, such as thermal spray and cold spray, also typically use powders within that size range.

This, however, has a serious implication on the amount of powders produced in an atomization process that meets the requirements and can be used in the process. Typically, for an industrial-scale gas atomizer working in a closed-couple system for processing non-reactive materials such as steels or aluminum alloys, the efficiency of atomization in the narrow 15-45 µm can be just 20 – 50 % depending on specific alloy, system, and parameters. For free-fall systems like Electrode Induction Gas Atomization EIGA, for processing reactive materials, the efficiency can be even lower, 10 – 30 %. Small-scale R&D atomizers often have even shorter runs and less stable parameters, further limiting yield.

That means that most of the atomized powder by gas atomization can be considered a waste consisting of undersized and oversized powder particles, partly usable by different technologies, further limiting efficiency and increasing energy consumption. While waste powders from non-reactive materials can usually be re-atomized in gas atomization, the reactive powders, such as Titanium or Nickel-based superalloys, are difficult to process. Powder producers and users must either store the hazardous powders in safe containers or pay for the material disposal.

Ultrasonic Metal Powder Atomizer, such as AMAZEMET rePOWDER, can be far more efficient, producing up to 80 % of powders in a narrow size distribution, like 20 – 63 µm. Very narrow distribution of atomized particles makes the choice of powder size range even more crucial, as a ±15 microns size range shift can increase or decrease yield up to 25 %. Still, the production capabilities of finer powders below 45 microns require the usage of higher frequencies, which is possible only for some materials. Additionally, the plasma module of rePOWDER can be equipped with a powder2POWDER module, enabling the re-processing of waste powders, minimizing losses of valuable feedstock materials.

That limited efficiency is the driving factor behind the high cost of the industrial gas atomized spherical powder for AM applications, strongly influencing the overall costs of metal AM processes. If Titanium Grade 23 ELI powders are to be used as a benchmark, 15-45 µm cut (~ 200 USD/kg) can be even 4 times more expensive compared to 45-105 µm cut (~ 50 USD/kg) used in Electron Beam Melting.

Summary

- Atomization Processes use a large amount of energy due to their inherent low energy efficiency, which decreases further as the smaller and smaller powder is to be atomized

- The Main Reason behind high energy requirements for gas atomization is the high consumption of inert gas, mainly Argon, which is produced in a liquefied/pressurized state, and is an energy-intensive process

- Ultrasonic atomization can be up to 10x more energy efficient process, mainly due to low inert gas consumption, but the technology is currently limited by relatively low productivity for R&D and highly valuable materials

- When purchasing powders or ordering atomization services, carefully consider what size range is necessary for your application. Narrow PSDs and smaller particle sizes will increase the energy and amount of feedstock needed for atomization processes, increasing the costs for the service