When people ask what is the hardest metal on Earth, they often expect a simple answer. In reality, the concept of hardness is more complex. Hardness refers to a material’s resistance to deformation, scratching, or wear, and it can be measured using different metal hardness scales. This means the “hardest metal” depends on how hardness is defined — whether in terms of scratch resistance, compressive strength, or overall durability.

In this article, we will review the hardest metals on Earth, compare their unique properties, and explore why certain metals outperform others in extreme environments. We will also discuss how advanced research and powder technologies are opening new possibilities for these remarkable materials.

Defining Hardness in Materials Science

In engineering, hardness describes a material’s ability to resist localized plastic deformation, meaning how well it can withstand scratching, indentation, or surface wear without permanently changing shape. It is not a single, absolute property but rather one that depends on how it is measured. For this reason, several standardized hardness tests exist, each highlighting different aspects of material behavior:

- Mohs hardness scale – one of the oldest methods, based on scratch resistance. Minerals are ranked from talc (1) to diamond (10). Metals typically fall between 2 (gold, lead) and 9 (tungsten carbide). While simple, it is qualitative and best suited for minerals rather than metals used in engineering.

- Vickers hardness (HV) – a micro- or macro-indentation test that uses a diamond pyramid pressed into the surface under a defined load. The resulting indentation is measured optically, and hardness is expressed in kgf/mm². This method is precise and works across a wide range of materials, making it useful for both thin films and bulk metals. For example, pure tungsten reaches ~3430 HV.

- Brinell hardness (HB) – involves pressing a hardened steel or tungsten carbide ball into the material under a specific load. The size of the resulting indentation determines the hardness value. Brinell is particularly useful for softer metals and alloys with non-uniform structures, such as cast irons, because it averages hardness over a larger area.

- Rockwell hardness (HRC/HRB) – measures the depth of penetration under load using either a steel ball (HRB) or a diamond cone (HRC). It is widely applied in metallurgy and manufacturing because it is fast, requires no optical measurement, and can be directly read from the machine. For example, hardened steels often score 60–65 HRC.

Each of these methods provides valuable but slightly different insights. For this reason, hardness data for the same metal can vary depending on the scale used. Engineers often compare values across multiple scales when selecting materials for wear-resistant components, cutting tools, or high-performance alloys.

For metals, Vickers and Rockwell are most relevant, as they capture resistance to wear and indentation under defined load for wide range of metals.

Candidate Metals for the Highest Hardness

- When discussing the hardest metals on Earth, several candidates stand out, each with unique properties that make them suitable for different applications.

- Tungsten is often regarded as the hardest pure metal. With an exceptionally high melting point of 3422°C and remarkable density, it maintains its hardness even at elevated temperatures. These features make tungsten indispensable in cutting tools, armor-piercing ammunition, and aerospace components operating under extreme conditions.

- Chromium is another contender, known for its outstanding wear resistance. While not as hard as tungsten in bulk, it is frequently used as a surface treatment in the form of chrome plating. This not only increases surface hardness but also provides excellent corrosion protection, especially for steels.

- Osmium, the densest naturally occurring element, is also among the hardest metals. It combines extreme compressive strength with significant hardness, but its rarity, high cost, and toxicity of certain compounds limit its use to highly specialized applications, such as precision instruments and electrical contacts.

- Titanium, in its pure form, is not among the hardest metals. However, its alloys demonstrate a valuable combination of relatively high hardness, low density, and one of the highest strength-to-weight ratios known as specific strength. These properties make titanium alloys vital in aerospace engineering, biomedical implants, and other advanced design applications.

Thus, in terms of pure metals, tungsten is most often recognized as the hardest, while osmium may surpass it in specific contexts, though its rarity and toxicity limit applications. Over time, however, engineered materials such as precipitation-hardened alloys, and advanced high-entropy alloys (HEAs) have demonstrated hardness values exceeding those of pure metals, showing that the hardest materials used in industry are often complex alloys rather than single elements.

Industrial Relevance of the Hardest Metals

The hardest metals on Earth are essential in advanced industries:

- Cutting and machining tools – high-speed steel (HSS) blades combine hardness with toughness, making them suitable for drilling and milling applications.

- Protective coatings – chromium layers extend component lifetimes.

- Extreme-environment components – tungsten heavy alloys perform in aerospace, nuclear, and defense applications.

While osmium is technically harder, it is rarely used due to availability and health hazards.

Hardest Metals in Powder Metallurgy and Additive Manufacturing

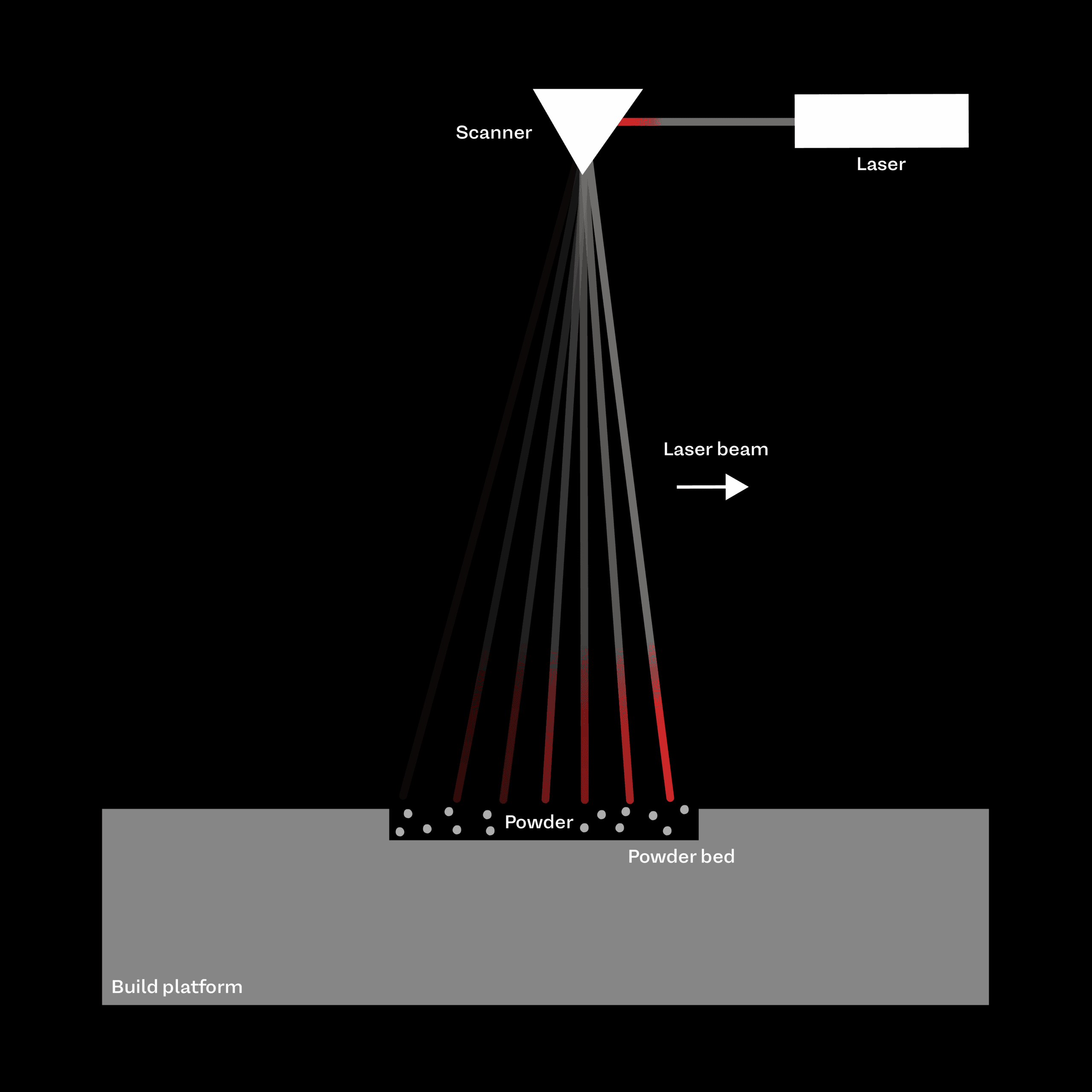

Modern applications increasingly rely on powder-based routes. By converting hard metals into metal powders, engineers can exploit their unique properties in additive processes such as Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF) or Electron Beam Melting (EBM).

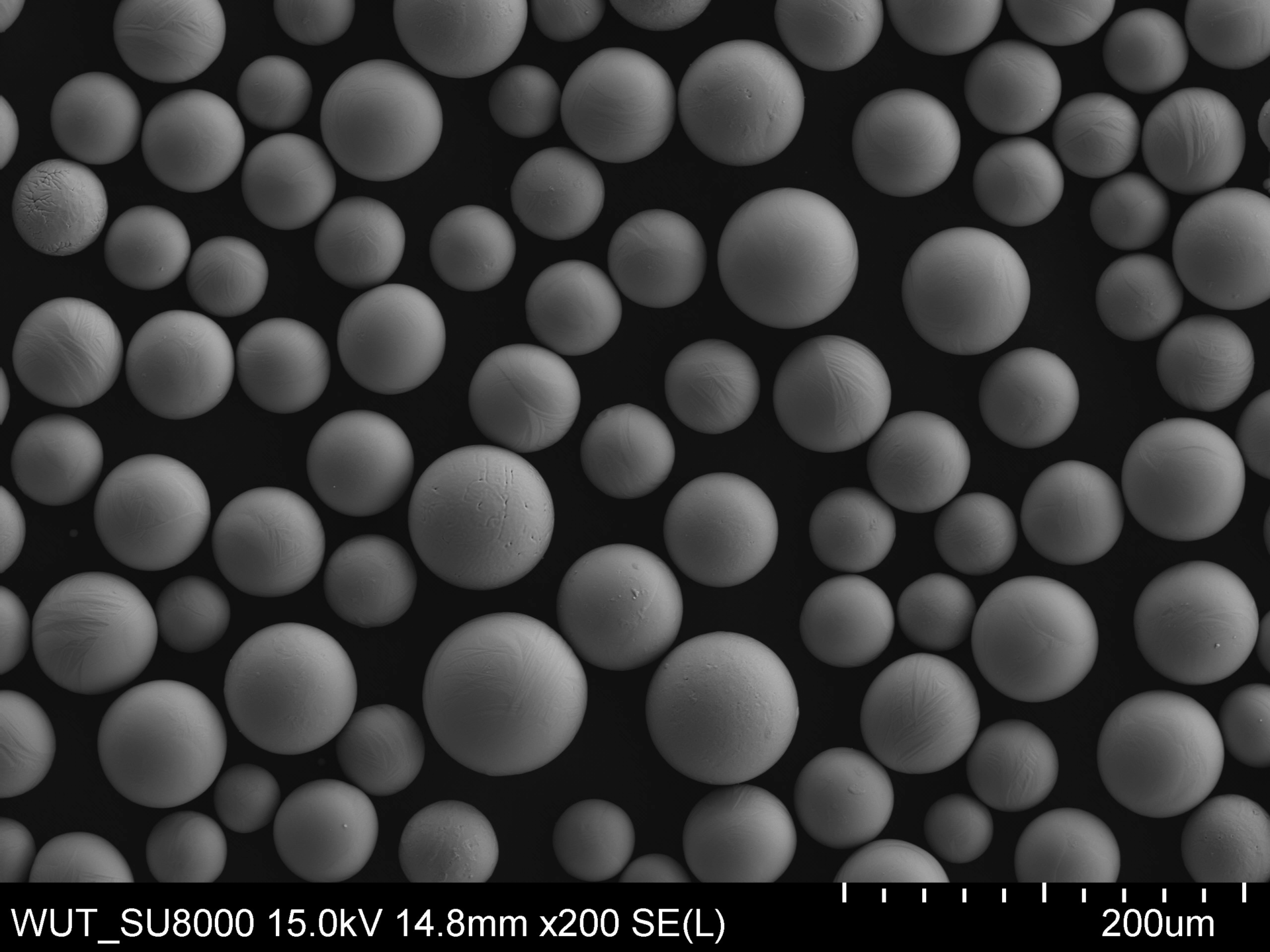

The performance of these powders depends on particle size distribution, purity, and sphericity. High-quality powders are essential for consistent layer deposition and mechanical reliability of printed parts. Learn more about metal powders and their role in modern manufacturing.

AMAZEMET’s Role in Research on Hard Metals

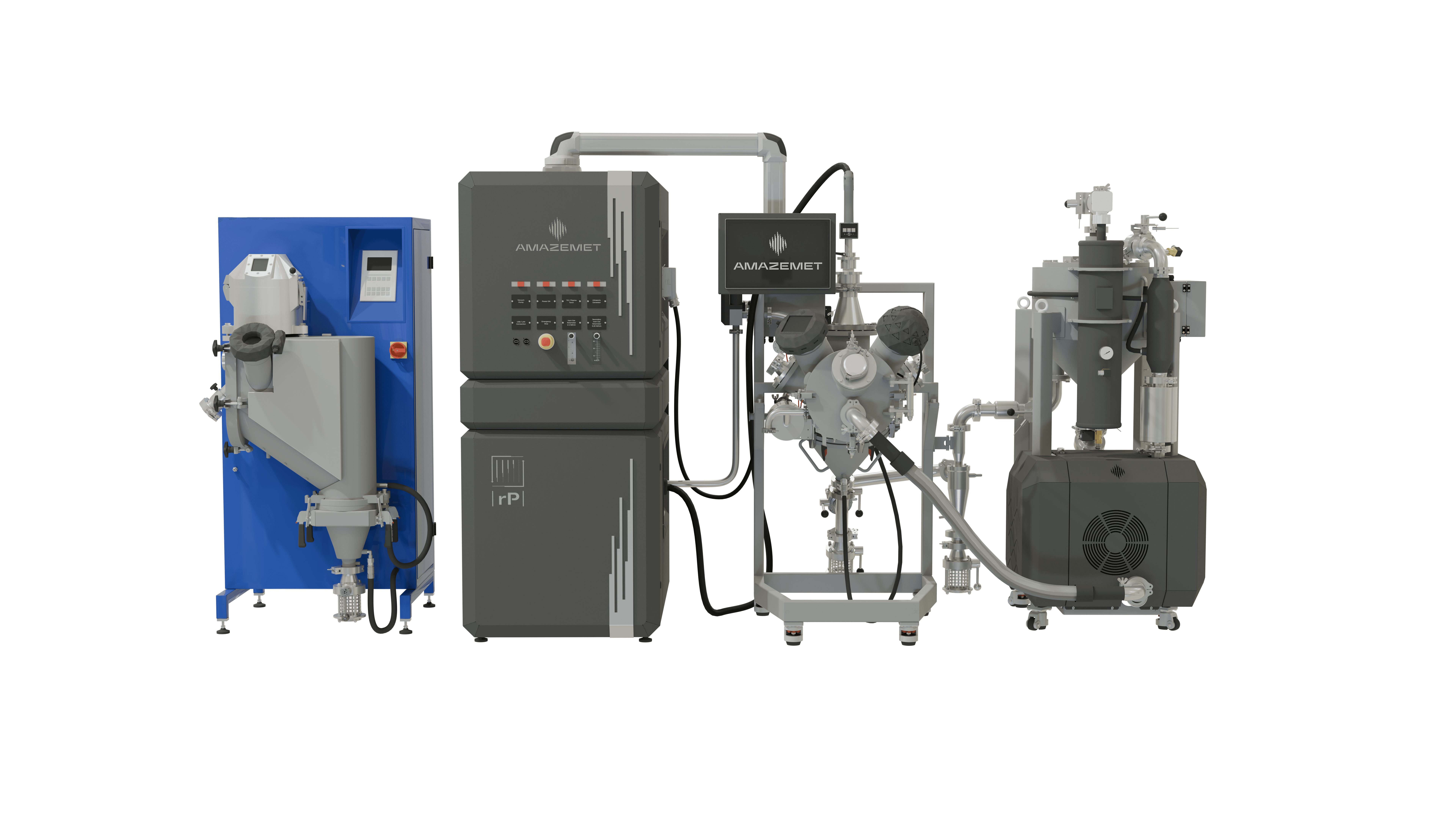

At AMAZEMET, we support research into the hardest metals on Earth by enabling controlled small-scale powder production. Our ultrasonic atomization technology allows:

- Processing of refractory metals and high entropy alloys into spherical powders.

- Tailoring of alloy compositions for specialized applications.

- Production of flowable, contamination-free powders for additive manufacturing trials.

This approach bridges the gap between fundamental research and industrial-scale deployment. While osmium and other exotic elements remain mostly academic, most of the alloys are within reach of our capabilities.

Conclusion

The hardest metal depends on the measurement method:

- Tungsten – generally recognized as the hardest practical pure metal.

- Osmium – potentially harder but limited in use.

- Chromium – excels in surface hardness.

- Titanium alloys – combine sufficient hardness with lightness.

From an engineering perspective, hardness alone does not decide material selection. The real challenge is balancing hardness with toughness, manufacturability, and resistance to harsh environments.

At AMAZEMET, we contribute to this challenge by delivering powder solutions that make the world’s hardest metals usable in metal additive manufacturing and advanced material research. If you are exploring high-performance alloys, discover how our expertise in metal powders can support your work.